Just because a film is dark doesn’t make it deep; in the post-Christopher Nolan landscape of superhero films, ‘dark’ can just as easily mean ‘dreary’. Violence for the sake of violence is dull and unsatisfying; unwarranted angst comes cheap. But in certain instances, a bare-fisted, bloody, no-holds-barred treatment is exactly what’s needed to get to the heart of a character, and to shy away from that would be to do all interested parties a disservice. Logan is a film that justifies its darkness and benefits hugely from its hard-R rating, but not necessarily for the reasons you’d expect. It’s a Wolverine film that doesn’t hold back, which seems to have made all the difference.

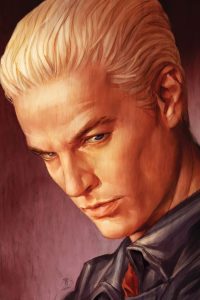

The Wolverine (aka Logan, aka James Howlett) has been a fan-favourite since he first appeared in the mid-1970s and carved out a legacy in Chris Claremont’s legendary X-Men run. The violence inherent to this grouchy, grudgingly noble character comes down to his physiology as much as it does his ominous back-story. Logan is a man-turned-weapon with an indestructible adamantium skeleton, a deadly set of claws and an unstable nature. He’s easily triggered and capable of extreme savagery. The X-Men films, shackled by PG-13 ratings, have assured us that he’s dangerous but have never before given audiences a full picture of what he’s truly capable of.

But it’s not the violence (this is an incredibly violent film) or the nudity (blink and you’ll miss it) or liberal use of the F-bomb (Professor X as you’ve never seen him, folks) that elevates Logan so far above its predecessors. It’s an overall loosening of restraints that allows the story to go places it never could have within stricter parental guidelines. Horrible brutality is perpetrated on children, and by children. No good deed goes unpunished, bad things happen to good people, and heroism runs parallel to slaughter.

Old Man Logan is no longer the wisecracking, beer-swilling, cigar-chomping character we’ve gotten to know over the past seventeen years worth of X-men films. He’s been beaten down by pain and loss (an unspoken tragedy lurks beneath the surface of the film) and his body is finally failing. He’s self-medicating with alcohol, but he’s weary, ready to move on. Mostly he just wants to be left alone.

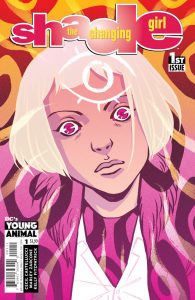

His only tether to his former life is a degenerating Professor X, whose powerful mind is now fragmented and dangerous. Their relationship has evolved to that of a father/son dynamic, defined by reliance and resentment in equal measure. They give each other fragile purpose, just enough to keep them both alive, but it won’t be enough to sustain them for much longer. This is when they meet Laura Kinney, a young mutant on the run from a shady military group, and everything shifts into high gear.

A film like Logan could only exist because a studio decided to take a risk; in this case, Fox took it on last year’s Deadpool. In rolling the dice on an R-rated Deadpool film, the Fox franchise planted a flag in largely uncharted terrain, inadvertently finding itself a new niche. Fart jokes aside, Deadpool was an incredibly important, game-changing superhero film that proved that a big budget and a broad audience aren’t the only prerequisites for box-office success. With the X-Men brand in a transformative phase, Fox needed a different direction, and with mature films like Deadpool and Logan, they seem to have found one. This is all the more reason that the X-Men property belonging to Fox rather than the Disney-owned Marvel brand is a good thing; Logan could never have existed under that umbrella, except perhaps as a Netflix series. Even then, Logan is a different beast altogether.

It’s hard to remember at times that Logan is a superhero film; it would be easy to imagine Best Performance nominations cropping up if this weren’t the case. It’s as much a western and a road movie, with a broken-down old gunslinger going on the run to help a fugitive cross the border to Mexico. It bears more similarity to director James Mangold’s acclaimed Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line than it does to his okay X-Men instalment, The Wolverine. Hugh Jackman, who has stated that he’s ready to retire the character after his tenth turn, simply is Logan; he has never given a better performance in this role. The same can be said for Patrick Stewart, hilarious and heartbreaking as a delightfully unfiltered Professor X. The supporting cast is also outstanding; Stephen Merchant is almost unrecognisable (in a good way) as the albino mutant Caliban, whose power is an ability to sense and track other mutants. Eleven-year-old Dafne Keen as Laura is spectacular in a role that would challenge actresses three times her age; she’s both subtle and wildly visceral and is utterly convincing either way.

The burning hope for most film-goers (as it was for this film-goer) is that maybe they’ll finally get a good Wolverine film; instead, they’re getting a great one. This is the ending that fans deserve. When it comes to dark superhero films, Logan might just be the best there is, and the most emotionally satisfying – even when it isn’t very nice.